The History of Indian Telecom Licensing — A Policy Perspective

Preface

The whole idea of writing this note is to analyze what went wrong with our licensing regime. Why we are in a situation where a serious player like VodafoneIdea is struggling to survive? What mistakes were committed which has led to this situation and what could have been done better? Finding answers to these questions is important, as knowing the past, empowers us to visualize the changes needed for the future. As George Santayana observed, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” (The Life of Reason, 1905). But the visibility of the past is always a challenge. As information is scattered all around in a disorganized form and unpalatable for consumption. The purpose of this note is to simplify this information so as to enable the reader to have a birds-eye view of what happened and why. How simple mistakes had a cascading effect on future policies. And these mistakes have now come to haunt us and have become hard to unwind. While writing this note I have made all efforts to share the links of the original references which I have used to weave this story, so that nothing is left for speculation. In order to keep the focus, I might have ignored many events which in my opinion is not central to the theme of this discussion. All efforts have been made to present data in a manner which easy to comprehend so that the real story does not get lost in the details. In order to do justice to the topic, I had to keep this note longer than usual but made all endeavors to maintain the flow of the story. Hope you find this useful.

1. Introduction

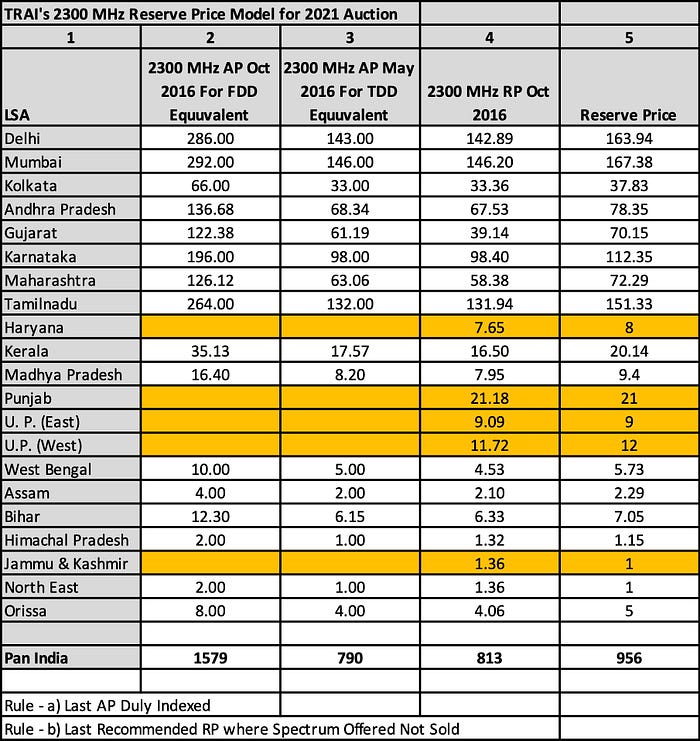

In the 1990s, DoT (Department of Telecom) was unable to cope up with the demand for telephone connections. As it needed huge investments, which was not within DoT’s powers to sustain. Hence, it decided to allow the entry of private entities into the telecom sector. It did so by invoking Section 4 of the Indian telegraph act of 1885, which authorizes the Indian Government to grant telecom licenses on such consideration and payments that it thinks fit. DoT chose to grant service-specific licenses by bundling spectrum with it, and this was a mistake. Why? All the issues that the industry had faced in the past and are facing today are directly linked to this decision. Since 1994, the DoT has issued multiple such licenses, whose financial terms and conditions (including rules for spectrum) kept changing with time — actually became worse, with some decisions even self-contradictory, picked totally out of context, and poles apart from International best practices. Later, on 15th Feb 2012, though the DoT delinked spectrum from the license (to be assigned through auctions), however, the obligations like high license fees, spectrum charges, etc (which were earlier imposed on account spectrum being bundled with the license) were not withdrawn. Instead, the DoT attached an additional burden on the operators (in terms of the high auction fees), thereby creating a huge barrier to entry — driving some serious players out of business, and converting those remaining as non-serious — discouraging them from expanding networks and offering quality services. Also, the sector was marred by continuous litigation. These were triggered by intrusive and ambiguous regulatory practices, done with an intent to enable maximum flexibility to the licensor to intervene and change regulation including the clauses of the license. By saying so I do not mean that the regulators didn’t justify their actions. They actually did, but the logic of these justifications was shallow and did not carry forward in time for the purpose of consistency — leading to faulty decisions. For example, in the 2016 auction, the use of the wrong multiplier of “4” for arriving at the reserve price of 700 MHz, and in 2012 & 2013, two different multipliers (“1.3” & “2”) for 800 & 900 MHz bands when both bands are with similar capabilities, (details on this are available in the section of 2012 auctions). This vitiated the business environment, increased transaction costs, caused uncertainty, and increased opportunities for regulatory highjack and manipulation. Some operators played opportunistically and tried to take undue advantage of these distortions, by supporting them when it helped them, but later the same distortions acted against their own interest. The purpose of this note is to critically analyze what regulatory mistakes triggered this situation, what kind of cascading effect it had on follow-up regulations, and how it hampered the DoT’s ability to undo that past damages, and what could have been done better.

2. Cellular Licenses (1994)

The foundation of it was laid by NTP-1994, with a key objective of enabling telecommunication within the reach of all. The first set of licenses were signed in the month of Nov 1994 on the basis of beauty context for the four metros — Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkatta, and Chennai for a 10 year period. The obligation to pay license fees is listed as under (Source — Bharti’s CMTS License Agreement).

2.1 License Fees -

Note that from the 4th year onwards one more clause was attached. I.e the licensor has to pay fees @ 5 lakhs per 100 subs per annum subject to the minimum as shown in the above table. This means that DOT was planning to collect at least Rs 5000/sub/year as license fees from the 4th Year onwards. The total license was for a 10-year duration.

Since spectrum was bundled with the license, the obligation was to pay spectrum fees to WPC and is described as under.

2.2 WPC Royalty -

It had two parts. A) Spectrum Royalty; B) BTS Royalty.

Spectrum Royalty was set as Rs 8,44,800/- per annum. The rate was Rs 4,800/- per voice channel. Now with 22 carriers of 200 kHz each for 4.4 MHz of GSM spectrum, and each carrier contributing to 8 voice channels, the total royalty was = 22 x 8 x 4,800.

BTS Royalty was set as Rs 100/- per Base Station per Annum.

Now assuming a concentration factor of 20% and ignoring BTS royalty, the total royalty load on the consumer from the 4th year onwards was Rs 5,960/- per annum (5000+0.20x4800).

2.3 Key Issues -

a) High License Fees were not in alignment with the objectives of NTP 1994, which called for telecommunication within the reach of all. As, from the 4th year, Rs 500/- of the consumer’s monthly bill was to be used up for paying license fees due to the government. Note, this did not include other fees due to the govt, like payment for usage of MW spectrum, etc. With such high license fees, how could have the operator expanded networks and the consumers afforded such services? Were the high license fees not in direct contradiction with the objectives of NTP-1994 which never called for maximizing government revenues?

b) DoT’s decision to sell “Permission” for offering a particular kind of service and bundling real Assets like the spectrum with it, laid the foundation of a flawed regulatory practice, which has become the genesis of all key problems that we had faced and continue to experience today. Be it the battle of “limited mobility” of 2002–03, or the 2G Scam of 2007–08. All have roots in this DoT’s decision to sell “Permission” which was just a paper document. Normally, spectrum should have been delinked from this “permission”, which should have been charged to cover only the cost of administration, and nothing more. Spectrum should have been auctioned separately. Doing so is an international norm. Article 6 of the Directive 97/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 April 1997 is reproduced below.

“Without prejudice to financial contributions to the provision of universal service in accordance with the Annex, Member States shall ensure that any fees imposed on undertakings as part of the authorization procedures seek only to cover the administrative costs incurred in the issue, management, control, and enforcement of the applicable general authorization scheme. Such fees shall be published in an appropriate and sufficiently detailed manner, so as to be readily accessible”

The Indian licenses also fell in the category of authorization, and DoT should have charged only administrative fees to cover the cost of administration. Anyways, the spectrum (bundled with the license) was charged separately by WPC.

TRAI had a logic to support the decision to charge higher revenue share as license fees, than just administrative fees. The logic was that since the spectrum was bundled with the license, fees paid (in terms of revenue share) to the government should reflect that fact (clause 5.4 & 5.5 of TRAI’s recommendation dated 23rd June 2000). But if this logic was to stay persistent, then why didn’t the DoT reduced license fees to a nominal amount when it started offering spectrum through auctions, and return generated a perpetual revenue stream that was at par with the license fees?

But what is wrong with selling “permission”? Because it did not serve the overall objective of the NTP which was to make telephony accessible to all. Actually, it did the opposite. It made services unaffordable and discouraged the operators from expanding networks. Why? Operators faced no competitive threats, as the DoT was restricting player’s entry into the market by imposing high fees. Permissions are just paper documents, and they didn’t guarantee access to physical assets, including spectrum (though spectrum was bundled however the access to it was not assured and given on an availability and need basis). These had to be obtained separately and had financial implications. Actually, the DoT should have reduced this barrier to entry by making the license accessible to all those who were interested in contributing and just set eligibility criteria high enough to prevent those nonserious. All assets like spectrum should have been sold through auctions from the beginning, but not with the intent of maximizing revenues, but to enable its efficient utilization. So that the spectrum is used and does not lie idle as we have today (more than 60% of the assignable spectrum today is unused). Check out this page which gives a graphical picture of all bands used today, and those marked “pick” spectrum there is lying used. As you read through this note you yourself will come to this conclusion.

3. Cellular Licenses (1995)

In Dec 1995, 34 CMTS Licenses were granted based on tendering for 18 telecom circles for a period of 10 years. In order to get access to the license, all players had to match the highest bid. The absolute value of bids for the various circles is embedded in the following picture (Source — Appendix 7, Table 11.1.4, Page 47 of TRAI’s CMTS Explanation Memo dated 23rd June 2000).

3.1 License Fees -

The highest bid was fixed as the license fees to be paid staggered over the 10 year period in the manner described in the following table. Note deferred payment schedule has been extracted out from the Birla AT&T License for Maharashtra dated 12th Dec 1995, and the same yearly % distribution is applied for all other circles in order to arrive at their deferred payment schedule.

3.2 WPC Royalty-

Unlike the 1994 license, WPC royalty was not embedded in the license but issued separately vide letter dated 20th July 1995. The formula for calculating annual royalty is as under.

Annual Royalty in Rs (R) = M x C x K +1200 x W

Where M = 4800; C = RF channels of 200 kHz; K = 8 (voice channels per carrier); W = 1000 for every thousand subs or part thereof. So if the spectrum is 4.4 MHz and there were 5 Lakh subs in the network then annual royalty = 4800 x 22 x 8 x 2000, i.e 42.24 Cr (more than 25% of the yearly LF payout).

Note, like in the 1994 license, the royalty for the MW spectrum had to be paid extra. The details of which are embedded in the WPC order dated 20th July 1995.

3.3 Key Issues -

The license fees were not only high but in NPV terms a large proportion of deferred payment value was skewed towards the initial years (approx 57% in the first 3 years). See chart as under.

While calculating the NPV payments I have taken a discounting factor of 18.5% (not sure what DoT used at that time, but it doesn’t change the overall picture). Doing so matches the numbers that TRAI has mentioned in its table Appendix 7, Table 11.1.4 dated 23rd June 2000 except for the circles whose totals have been marked yellow (last row).

Then WPC royalty was a large proportion of the license fees and was independent of the type of circle, i.e lower potential circles had to pay fees at the same rate — making these circles totally unviable.

All bidders were asked to match the highest bid, even if their bids were miles apart — for example in Gujarat Fascel’s bid was 68% of Birla AT&T’s bid, and in Maharashtra BPL’s bid was 12% lower than AT&T’s bid, etc.

Deferred Payment led to speculative bidding as a large proportion of the bidder’s obligations (license fees and spectrum royalty) were to be paid in the future, thereby motivating bidder’s to bid high — there was no compulsion on them to arrange cash immediately. Due to this reason, it is widely accepted that deferred payment leads to speculative bidding and therefore is considered as a poor auction design metric. In spite of this fact, it is strange that TRAI in their recommendation dated 23rd June 2000 (clause 4.11) believed that auctioning the “% number” for revenue share will lead to a better auction design. This understanding was a mistake, as all the earlier auctions (before 2001 and later after 2010) were modeled based on deferred payment, and we know what happened to them. Also, S-Tel on 5th Nov 2007, had offered to pay a higher price in the shape of an additional revenue share. The offer was enhanced with a stipulation to raise it further if there was a counter bid (Source — CAG Report of 8th Oct 2010, para 5.2). On the basis of this offered, the CAG calculated the value of 35 dual tech licenses and 122 new licenses given in 2008 at Rs 65,909. More on this as you read through.

Translating these bids (in 1995) at todays’ prices (2021) gives us the following picture.

The intensity of these bids can be clearly reflected from the fact that the license was bundled with just 4.4 MHz of GSM spectrum in the 900 MHz band and royalty payments on the spectrum were on top of this bid. Please note that if we compare these bids prices with the current reserve price of the 900 MHz band, these are much more than double (on a per MHz basis).

The license was just a paper document, and bidders were actually bidding for the right to access spectrum, and without access to spectrum, the license did not have much value attached to it — unless the license was used as a means to restrict the entry of new players in the market. And DoT was exactly doing that, and the players paid from their nose for this restriction. As you read through this note you will see how DoT used the license as a tool to restrict and allow the entry of players into the market. And how the practice was misused by Raja (the telecom minister in 2007/08) to subsidize the entry of new players in the market, thereby laying the foundation of the 2G Scam and its subsequent impact on the Indian spectrum auctions.

4. Basic Service License (1997)

In 1995, bids were also invited for basic telephony services with the license fee payable for 15 years. This license empowered the operators to provide both fixed-line and wireless-based basic telephony services. Six licenses were granted in the year 1997–98 through a process of tendering.

4.1 License Fees -

DOT’s accepted bid along with the payment schedule is embedded in the following picture.

Note the except AP whose values are picked up from Tata’s BTS License Agreement dated 4th Nov 1997. For the rest of the circles, the data has been built based on the license fees information provided in the TRAI’s recommendation dated 31st Aug 2000 on page 22/23. Here, TRAI has provided data on license fees paid by BTS operators for 2 years which was supposed to become an entry fee for their migration into the revenue share regime. The estimation of fees for the rest of the period has been done based on Tata’s BTS Agreement.

The value of the license fees at 1997 prices (assuming the same discounting factor as was used for CMTS, i.e 18.5%) is embedded in the table under.

Now when we compare these numbers with those of CMTS license fees of 1995 by escalating the CMTS values by a factor of 1.5 to align with 15 year period of the BTS license period we have the following picture.

One can clearly see that the bid values of the BTS license with restrictions on usage of wireless spectrum for the last mile, and with no “limited mobility” provision for the full SDCA (Short Distance Charging Area), were very high in all the circles except Gujarat when compared on PV of the respective years. This looks really strange. On top of this, the BTS operators were supposed to pay 2% (0.5% towards administration and 1.5% towards R&D cost) of the Gross Profit of their business every year (Page 75 of the Tata’s License Agreement Dated 4th Nov 1997).

4.2 WPC Royalty-

Details of the WPC royalty rate for the Basic Services Licenses of 1997–98 are not available. But I doubt these will be dissimilar from those of CMTS royalty rates of 1995.

4.3 Key Issues -

Most issues are similar to those of the earlier CMTS license, but payment obligations for the BTS license were more stringent when compared with those of the CMTS. When compared in PV terms, the cash outflow of the BTS licenses was more due to the higher value of yearly payments which included 2% of gross profits and coupled with spectrum royalty payments. Hence, it is not clear why bids were even made for these 6 circles and why no bids were made for the remaining circles.

5. Cellular & BTS License (2001)

In the year 2001, the 4th Cellular license agreement was signed. The was an outcome of a multistage auction process carried out in the backdrop of NTP-1999. Copy of Birla A&T license agreement dated 10th Oct 2001 is embedded here as a reference. Also, It is clear from the above analysis that it was not possible for the incumbent operators (both CMTS & BTS) to run services when such high license fees were to be paid to the Government. What added insult to the injury is that the old license fees were structured such that its values increased as the operators took more subscribers. In other words, the operators were prevented from taking more subscribers. Why? On the one hand, handsets prices were high, and on the other hand, they were forced to keep tariffs high to make up for the regulator costs (old CMTS license fees from 4th year onwards, and WPC royalty) which were structured on a per-subscriber basis. These issues were clearly visible to the Government — leading to the migration package dated 22nd July 1999, which the operators accepted unconditionally.

5.1 License Fees -

As per the migration package, the license fees were structured in two buckets.

- Entry Fee — This for the incumbent operators was the total license fee (on yearly dues) paid before the signing of the package. And for the new CMTS operators, it was decided through a competitive bidding process (4th Cellular License).

It is noteworthy, that the operators were so desperate that they signed the migration package unconditionally without even finalizing the commercial, especially a) % Revenue Share b) Definition of “Revenue”. This is the genesis of the current debate on AGR definition which has put Vodafone-Idea’s survival at risk and diminished the competitiveness of the telecom industry.

Comparison of Entry Fees Paid by a new CMTS operator (2001–4th Cellular license) vs the incumbent CMTS licenses (before 1999) is embedded in the table under (Source — Page 34/35 of TRAI’s Recommendation Dated 26th Oct 2003).

It can be seen that in most circles the incumbents end up paying much higher entry fees compared to the new 4th CMTS operator who entered through a multistage bidding process. On a Pan-India basis, the entry fee paid by the 4th Cellular Operator was Rs 1633 Cr. Also, note that the entry fee values of the incumbents are the average of fees paid by various operators, as each incumbent operator paid slightly different entry fees.

Comparison of Entry Fees Paid by a new BTS operator (2001 — New BTS license) vs the incumbent BTS licenses is embedded in the table under (Source — Page 34/35 of TRAI’s Recommendation Dated 26th Oct 2003).

Again one can see the incumbents paid a very large entry fee compared to the new BTS operators. Please note, unlike the 4th cellular whose entry values were decided by an open bidding process, the entry value of the new BTS operators was fixed by TRAI by its recommendation dated 31th Aug 2000. Also, note that the new entry fees for the CMTS operators were much higher than what was recommended by TRAI for the BTS operators.

2. Revenue Share — This was a certain percentage of their revenues — the definition and quantum of which was to be decided by TRAI through an open consultative process. And based on the TRAI’s recommendation DOT issued guidelines on 25th Jan 2001 for the entry of both new CMTS and BTS operators.

For CMTS operators the revenue share was decided as 17% of the AGR (adjusted gross revenues) except for A&N. Note — DOT has been charging 15% as provisional revenue share till the final decision was made.

For BTS operators the revenue share was decided as 12% for Cat A circles, 10% for Cat B circles, and 8% for Cat C Circles (page 9 annexure 1 of BTS guidelines).

Again, two different licenses are charged grossly different fees with the technical capabilities to provide similar services. It is like laying a platform of manipulation and arbitrage, thereby steering the industry from the trajectory of smooth waters into rough seas — all attributed to DoT’s decision of giving service-specific licenses.

5.2 Spectrum Allocation & Royalty -

WPC issued a detailed procedure for allocation of spectrum & royalty for BTS operator vide an order dated 23rd March 2001. The summary of the order is below.

Spectrum in 800 MHz (824–844/869–889) on FCFS basis, max 2x5 MHz in 800 and or 1900 MHz band, and then in steps of 2x1.25 MHz after meeting rollout obligation except for Delhi. In Delhi one chunk of 2x1.25 MHz after meeting 2 Lakhs subs and an additional chunk of 2x1.25 MHz after completing 3 Lakhs subs. Spectrum royalty was fixed as 2% of AGR.

WPC also issued an order for allocation of spectrum & royalty for the 4th CMTS operator vide a letter dated 24th Dec 2001.

4th CMTS operator to get 2 x 4.4 MHz spectrum in 1800 MHz band to start with, but can be assigned an additional 2x1.8 MHz with an additional 1% revenue share of AGR. Hence, the total spectrum royalty for a CMTS operator holding a 2x6.2 MHz spectrum in the 1800 MHz band will be 3%.

WPC issued an order for allocation of additional spectrum & royalty for all CMTS operators vide an order dated 1st Feb 2002.

Additional spectrum to CMTS operators (beyond the initial 2x4.4 MHz) will be in blocks of 2x1.8 MHz. Till 2x6.2 MHz the royalty will be 3% of AGR (1% more for 2x1.8), and beyond 6.2 MHz the CMTS operator has to breach 5 Lakhs in the service area and will be charged additional 1% royalty on AGR, i.e the total royalty will become 4% of AGR.

5.3 Key Issues -

After the migration package, the situation becomes murkier than before and the issues attached to selling “permissions” became more visible. Why? Two different license streams were working with similar technical capabilities but with totally different fees. For CMTS the entry fees and revenue share were much higher compared to those of the BTS. Also, the CMTS entry fee was decided by open auction and those for the BTS were decided administratively by TRAI. This is when there was no technical barrier for the BTS operators to provide similar services (at par with the CMTS operators), however, this capability was artificially restricted by regulation. But for how long? History is a testimony that whenever a regulator tried to artificially limit the capabilities of technology, it has invited trouble and controversy. How can India be an exception? What follows next is a direct outcome of selling “permission”, and imposing “artificial restrictions”, which otherwise could have been easily avoided.

6. Unified Access Service License (2003)

Battle lines were drawn between the CMTS and BTS operators. Since the BTS operator was given the same quantum of spectrum in similar bands they had full capability to offer comparable services at par with the CMTS operator. Also, they discovered innovative ways to circumvent the artificial regulatory barriers imposed on them, like over the air dynamic activation of WLL subscribers outside his/her SDCA — leading to virtually full roaming. This resulted in litigation leading to DoT issuing the guidelines for UASL & CMTS on 11th Nov 2003.

6.1 License Fees -

- Entry Fee — The new guidelines allowed both the CMTS and BTS operators to migrate to the new Unified License Regime. This decision was though technology neutral on paper but got the industry totally divided on the basis of technology. This was mainly because of different spectrum assignment rules for GSM and CDMA operators (more on this as you read through). CMTS operators behaved as if they are married to GSM technology and the BTS operators to CDMA (operators use technology as a tool to deliver services and should NOT act as its proponents — the direct outcome of faulty regulation). For CMTS no additional fees were charged, but the BTS operators had to pay the difference between what CMTS operators paid and what they paid as entry fees to start with. The following table gives the picture (Source — Annexure 1 of UMTS & CMTS Guidelines dated 11th Nov 2003).

For Reliance the difference worked out to be Rs 1581 (Rs 1096 Cr LF + Rs 485 Cr Interest on delayed payment). For Tata, it was Rs 545 Cr. For Bharti, the number was Rs 487 Cr. For Shyam Rs 3 Cr and for HFCL 0.

2. Revenue Share — 12% of AGR for Cat A Circles, 10% of AGR for Cat B Circles, and 8% of AGR for Cat C Circles. Note that this was a relief for CMTS operators as their revenue share was brought down from 17% of AGR to the above levels (Source Page 25 of TRAI’s Recommendation on UL dated 27th Oct 2003).

6.2 Spectrum Allocation & Royalty -

Spectrum allocation as royalty rates to this date is assumed to be based on earlier WPC orders, and no new information in this regard is available in the public domain.

6.3 Key Issues -

a) The migration package has enabled DOT to extract more fees out of the operators than what they would have if the existing (fixed license fees regime) continued. On 27th Oct 2003, the TRAI, by analyzing data from 1999 till 2006, showed that operators have gained Rs 4565 Cr (as per NPV of the year 2003) caused by the migration. But my analysis (based on past and current data 1999–2021) points to a fact which is just the opposite. Actually, the industry has lost Rs 6.33 lakhs Cr (at the current value of money) due to this migration. Note — this does not include the additional license fees (including interest and penalties) collected by DoT on account of its recent victory in SC on the AGR definition. The details of my analysis are embedded in the table below.

The assumptions used in the model are listed below the table as shown above. To enable a realistic comparison (between old and new regime), I have raised the old regime upfront fees considerably — doubling it every four years to map with the optimistic value of what the govt would have charged if the regime had continued. The new regime fees are based on TRAI data (Page 26 of 27th Oct 2003), and thereafter, it is all actual data. Also, 8% has been used as a cost of funds for translating past money to the current value.

b) The migration package triggered nasty litigation between the DoT and the operators on the definition of “revenue”, the % of which the operators needed to pay as license fees. This litigation lasted for more than 20 years and has the potential of destroying the competitiveness of the Indian Telecom Industry by risking the survival of a key player (VodafoneIdea). This is detrimental to the interest of the consumers. The details of this dispute are available in my note titled — Indian Telecom’s AGR Tangle — Who is at fault?

c) The definition of “revenue” of the migration package has impacted the operator’s ability to optimize the cost of operations. Why? The operators are unable to have business arrangements with each other due to the doubling of license fees obligation to the govt. This is explained in my note titled — The AGR System — A Bottleneck for Motivating Investment. And because of this reason, the VNOs have failed to take off. See my earlier notes on this topic — How Effective is the VNO Guidelines? & VNO & Spectrum Sharing etc have failed to take off, but why?.

d) DoT’s new UASL guidelines dated 11th Nov 2003, created a reference for granting cellular licenses also administratively. Earlier (before the issue of these guidelines) only BTS licenses were given administratively. Please note that no rules were publically notified on the criteria to be used in case multiple operators applied simultaneously. This laid the foundation of the 2G Scam of 2007/08.

e) UAS License further exposed the ills of selling “service-specific” licenses, as it laid the foundation of the battle of technologies (CDMA vs GSM). It also created a framework for giving CDMA operators half the quantum of spectrum compared to the GSM operators. The logic used — CDMA was more efficient when compared to GSM. As per DoT, in order to preserve “level playing” such conditions were necessary. Even if it leads to spectrum lying idle, and the consumers deprived of benefitting from the capabilities of the CDMA technology. In the end, CDMA was prevented from leveraging its Data capabilities, lost its brand value, and slowly evaporated from the market.

7. New Cellular Licenses (2007/08)

Just like the “Limited Mobility” battle led to the UASL guidelines of 11th Nov 2003, the battle for “Dual Technology” led to the entry of the new cellular license of 2007/08. But what motivated the CDMA operators to opt for the GSM spectrum? As mentioned above, the genesis lies with the technology-specific spectrum assignment policy of the government. As per WPC’s order dated 10th Dec 2004 for CDMA, & 29th March 2006 for CDMA, & 29th March 2006 for GSM, CDMA was given approximately half the quantum of the spectrum compared to GSM for meeting similar subscribers numbers. These WPC orders are summarized in the chart under.

The impact of this order is clearly visible in the chart below which shows that the GSM operators were assigned twice the spectrum compared to the CDMA operators. This data is till June 2007 (Source — Pages 158–164 of TRAI’s Recommendation Dated 28th Aug 2007). CDMA operators were unable to unlock the full potential of their technology as the spectrum assignment criteria (which was voice-based) ensured that they cannot launch EVDO (data) services. Note — EVDO was the first technology that brought the capability of the real internet on phones. Unable to differentiate, CDMA as technology was no longer attractive, and it lost its brand value — motivating the CDMA operators to seek the GSM spectrum.

The reason for this differential treatment between GSM and CDMA on spectrum assignment was due to the fact that CDMA was more efficient in their ability to use spectrum and therefore needed less spectrum compared to GSM. So even if the spectrum in the 800 MHz was lying vacant, it was not assigned in order to maintain a level playing field between GSM and CDMA. This was bizarre logic, unheard anywhere else in the world on account of the battle of “Limited Mobility” (fought between the GSM and CDMA operators for respective competitive advantage). COAI alleged that the CDMA operators had given an affidavit in the court that CDMA technology was five times more efficient than GSM, so as to create solid justification for their case in TDSAT, where COAI challenged the so-called “Backdoor Entry” of the CDMA operators. But what they didn’t tell, or CDMA operator could not advocate publically, is that the efficiency data shared with the court on 27th May 2003 was contextual (it was for 2x10 MHz spectrum), and didn’t cover the Indian context where the spectrum given is minuscule, i.e only 2x2.5 MHz was to start with. Anyways, such bizarre arguments from both sides led to a regulatory practice (of penalizing efficiency) that had never been practiced anywhere in the world, thereby depriving the consumers of harnessing the full capabilities of technology. And this was a direct outcome of DoT’s selling service-specific licenses, which artificially restricted the operators from leveraging the full capabilities of the technologies. And this was practiced by granting vital assets (like spectrum) administratively through rules (technology-specific subscriber-based criteria) that were unheard of anywhere else in the world. All this was done in the name of maintaining a “level playing field”, and without caring for the consumer's interests.

7.1 License Fees -

The Entry Fee of these licenses was the same as those which were decided in 2001 by the 4th cellular auction (Approx Rs 1633 Cr). The details of the entry fees in on page 21 of the new UASL guidelines date 14th Dec 2005, extracted below for easy reference. The total for all circles works out to be Rs 1658.57 Cr. Why this difference from Rs 1633 Cr? Because in some circles were clubbed together with metro like WB with Kolkatta, and in some, there were no bidders in 2001.

The Revenue Share was 12% of AGR for Cat A Circles, 10% of AGR for Cat B Circles, and 8% of AGR for Cat C Circles.

7.2 Spectrum Availability (Issues)-

But the key barrier to the entry of new operators was not the entry fee or spectrum royalty, but the availability of spectrum in 900 & 1800 MHz bands. The total spectrum assigned to various operators along with their subscribers holding till June 2007, is shown in the table below (Source — Pages 158–164 of TRAI’s Recommendation Dated 28th Aug 2007). This data is of 180 CMTS & UASL operators as of July 2007 (page 12 of the same recommendations).

But why spectrum was a barrier, when the 900 & 1800 MHz band for GSM put together had 100 MHz of spectrum? And from the above table, it is clear that 60% spectrum was left unassigned.

This was on account of two reasons.

a) Spectrum Was Earmarked For Growth

On 29th March 2006, WPC came out with an order to lay out the plan for allocation of spectrum for the GSM operators. See under.

After mapping the subscribers’ numbers (till June 2007) with the WPC criteria, it is clear that the market leaders had enough subscribers then to stake claim up to 2x15 MHz of GSM spectrum. On top of it, there were new UAS Licenses (22 Nos) issued in Dec 2006, waiting for minimum spectrum (4.4 MHz) to start services. This means that if this claim of the spectrum was to be honored, then it was impossible to introduce new players in the market.

b) Spectrum Was Held By Defense

65% of the spectrum in the 900 & 1800 MHz band was actually held by the defense at this time. Initially, 100% spectrum was held, but DOT was able to coordinate some spectrum from the defense in 1994 & 1999 for the introduction of cellular services. Later in 2004, more spectrum was requested by DoT, but it didn’t result in sufficient spectrum and whatever was coordinated was on a city/district basis. Thereafter on 7th Dec 2006, a committee of GOM (Group of Ministers) was set up to oversee the progress of this release. This resulted in the Defense seeking an alternate OFC network (NFS — Network For Services) from DoT, in return for its vacating spectrum. However, the progress on the OFC network had been always was much behind schedule, hence it was not obligatory for the defense to release this spectrum. Even today, a large part of the OFC network promised by DoT then is still lying incomplete.

7.3 Spectrum Availability (Resolution) -

As discussed above, in order to enable the entry of new operators one needed to act on two key issues, a) nullify the claims of the incumbent operators of additional spectrum and b) get the defense to vacate spectrum in the 1800 MHz band. In order to facilitate the former, the TRAI’s recommendation dated 28th Aug 2007 came as a rescue. In this recommendation, TRAI had proposed to raise the subscriber-based criteria for both GSM and CDMA operators multiple times compared to the earlier WPC’s order of 29th March 2006. See charts below.

From the above charts, one can clearly see that TRAI had proposed a much higher number of subscribers for enabling the operator to get incremental spectrum. It is even alarming to see that the disparity between CDMA and GSM criteria has been further increased, thereby squeezing the CDMA operators into a much lower spectrum compared to their GSM counterparts. The TRAI’s recommendation was notified by WPC in their order dated 9th Jan 2008 for both GSM and CDMA operators.

As regards vacating defense from the 1800 MHz band, in my view coalition government politics played an important role. The DOT was managed by A Raja, who was a DMK representative, and the Defense was managed by a representative of Congress. Raja was able to extract spectrum from defense, even when DoT did not fulfill its promise of delivering the NFS network. Thus, the vacation of spectrum in the 1800 MHz band paved the entry of new and dual technology operators.

7.4 Spectrum Royalty -

The spectrum royalty prevalent at that time has been captured by TRAI’s Recommendation Dated 28th Aug 2007 on page 51, reproduced below.

One can see from the above table that the spectrum was charged at the same rate from 2x6.2 MHz to 2x10 MHz, i.e the royalty rates were the same for both 2x8 MHz and 2x10 MHz slabs. This helped only the GSM operators, as the CDMA operators were never given spectrum beyond the 2x5 MHz slab through the administrative process, thereby punishing the CDMA operators for their efficiency.

7.5 Key Issues -

1. FCFS policy failed miserably- TRAI’s recommendation of 2007 (which freed up spectrum from those reserved for incumbents), and followed by DoT’s public announcement of giving licenses to new players, dismantled the existing FCFS policy and made it totally dysfunctional. But why? Wasn’t FCFS a time-tested policy and DoT had been using it to give licenses since 2001, first to the Basic Service Operators (at rates recommended by TRAI), and then to Cellular Operators from 2003 (at rates discovered in the 2001 auctions)? The key reason for FCFS breaking down was due to the fact that it worked only when one player applied at a time, and NOT when multiple players apply simultaneously. The reason — FCFS had no built-in mechanism to break the stalemate (who to grant license and who not to) which happens when many players apply at the same time. Even if there were any, (like date of application, etc) it was never formally notified. Actually, the DoT was confused. This is clearly evident from the letter dated 26th Oct 2007 sent out by it to the law ministry for seeking its approval on the best of the legally tenable alternative to deal with the flood gates of applications triggered by TRAI’s recommendation and its earlier announcement. The law ministry on 31st Oct 2007 returned the reference without giving any conclusive opinion. The problem actually got aggravated by the fact that access to just the UAS License did not guarantee the assignment of spectrum. Spectrum was given based on a separate queue, thereby making FCFS not just a single-stage process, but a three-stage process till the assignment of the spectrum (See WPC’s FCFS order dated 23rd March 2001). Stage 1 was the issue of LOI (Letter of Intent), Stage 2 was the issue of the license subject to meeting LOI conditions (which included payment), and Stage 3 was the assignment of the spectrum (WOL — Wireless Operating License). This means anyone applying for a license may be ahead in the queue in the earlier stages but might get pushed back in the queue in the spectrum assignment stage. In other words, whosoever fulfills the condition of the LOI first, gets to apply for the spectrum first, and therefore his probability of getting the spectrum is higher. Now you know why there was a fistfight at the payment counter in DoT when the window was opened (in 2007). And why Raja meticulously controlled the opening and closing of the window only for a short duration of time. Because each operator wanted to pay first to be first in the queue for spectrum assignment. It is natural to question why TRAI could not visualize this situation when it recommended that 800, 900, & 1800 MHz bands should not be auctioned but only be assigned administratively? And even if it did, then why did it not spell out what rules need to be followed (for assignment) when multiple operators apply simultaneously? And Why Raja did not see through this lacuna and continued with the faulty FCFS policy and didn’t choose to rectify it?

2. CDMA Technology Got Killed — TRAI’s recommendation of enhanced subscriber criteria for CDMA (compared to GSM) further increased the disparity between the two, and virtually killed the CDMA’s key strength of offering internet (data) services. Spectrum is the foundation of cellular business, one cannot micromanage it in the manner our regulators did, that too in quick intervals of time. Note, that TRAI revised the subscriber-based to multiple times within a window period of just 1.5 years of the WPC’s order dated 29th March 2006. Such kind of fiddling is unheard of anywhere else in the world, and it destroyed operator confidence and opened opportunities for regulatory highjack and manipulation — very detrimental for the health of the overall business. Auction of license (mere permission) in 1999, and later in 2008 giving it away at a throwaway price (entry fee), empowered the regulatory to keep tampering with allocation criteria, thereby picking winner and loser in the game.

3. Overhyped Loss Numbers Stalled Future Spectrum Pricing Reforms — Though revenue maximization shouldn’t have been the intent, however, these licenses were just given at thrown away prices with valuable spectrum attached to them. But what was the quantum of this loss? Let’s calculate.

From the above one can see the total collection to the govt @ 2001 prices was approximately Rs 11K Cr. Now if we did a 10% escalation year on year for 7 years, the total would have worked out as Rs 21K Cr. So the real loss was just Rs 10K Cr? But what about the clamor of Rs 1.76 Lakh Cr loss as worked out by the CAG Report of 8th Oct 2010? In its report, the metric that CAG used to calculate the loss was speculative and noncontextual. For example, using the 3G auction prices as a reference to calculate the loss was totally incorrect. The reader will see for themselves, as they read through, that the main reason for the high 3G auction price can be directly attributed to these subsidized licenses (the TRAI in its recommendation of 2013 acknowledged this fact). And the use of price metric of S Tel % revenue share offer, and Unitech & Swan equity sales was also wrong, as these price quotes were for enabling entry into the market, and not for just spectrum alone. Also, CAG never chose to use the indexed prices of the 2001 auction for calculating the overall loss as one of the options. Why? As indexing past auction prices to arrive at the current reserve price has been a norm followed by regulators routinely. An economist will tell you that putting all the 2G spectrum for sale (even in small quantum over time) would not have resulted in such high revenues, as spectrum auctions are mostly contextual, and driven by many factors, and the most important one is the need of the players to preserve their competitiveness in the market. Else, why have most spectrum offered in the auctions since 2012 remained unsold? So the real loss caused by Raja (if any) was not Rs 1.76 Lakh Cr, but just only Rs 10 K Cr!

4. Exponentially Escalated Price of 3G Auction of 2010 — Unfortunately, the 3G auction was held in the backdrop of this entry (entry of new operators at a subsidized rate in 2008). Six to Eight operators entered the sector, which was in addition to the already existing operators. The number of slots offered in the 3G auctions was just three, and it was chased by 10 to 14 operators. Naturally, the demand was very high compared to the supply — pushing the 3G price exponentially high (5 times the reserve price set by DoT). This was extremely harmful to the industry, as it artificially drove up the spectrum prices, and pushed some of the serious players to bankruptcy.

The Notion of “Level Playing” was Grossly Misunderstood— This you might have already noticed by now, and will continue to observe as we proceed forward with this discussion. Even if you try, it is not possible to maintain a “level playing” condition. It is nothing but a myth. The Reason — Take the example of land prices, it keeps escalating, but businesses entering at different points of time, do not get to acquire it @ the same rate or method that their competitor has purchased. Some are auctioned, and others are purchased on lease. Also, some are taken on rent. All in different prices depending on market conditions. So what was the compulsion for Raja to perpetuate FCFS policy for the newcomers when a novice will tell that it can’t be implemented (without creating controversies) when many operators apply simultaneously? Also, why there is a need to level the playing conditions if the market conditions have changed dramatically? To stretch this even further, what is the need to charge the same license fees from a new entrant, when the incumbents playing in the market have the benefit of an early entry? Hence, the objective of regulation should be to drive larger consumer interests — i.e predictability, transparency, efficient use of resources, ease of doing business, and not constantly fiddling with spectrum assignment criteria to the disadvantage of a more efficient technology (like CDMA) in the name of maintaining “level playing” condition, even if that meant keeping large blocks of spectrum lie idle and unused. Too much focus on selectively manipulating business metrics in the name of “level playing” is the key defect of our licensing regime.

5. Dual-Tech Companies Got Special Treatment —

As you will read through you will find that all licenses given by Raja were ordered canceled by SC, except a few selected. Why? Looks like they got lucky or otherwise?. The rules were set such that some selected dual technology companies (like Reliance) were allowed to take the LOI (Letter Of Intent) much in advance compared to others. The LOI empowered them to pay up entry fee (Pan India Rs 1650 Cr) one more time to get access to the GSM spectrum. This LOI was issued to Reliance much earlier i.e on 19th Oct 2007, compared to the other new UASLs which were issued on (10th Jan 2008) — giving Reliance enough time to pay in comfort, as they didn’t have to queue in for making payments as the other holders of the LOI had to. Some might question how can the DoT give LOI to Reliance much earlier than other new players? As per my understanding, Reliance had formally requested for GSM spectrum on 6th Feb 2006, much earlier before the DoT’s formal announcement of the Dual Tech policy (18th Oct 2007). But Tata made a similar request on 22nd Oct 2007, but DoT kept that request pending. It is like saying that if you happen to initiate a request first, the fulfillment of which needed a policy change, which the GOI happens to announce sometime in the future, then your request that you made before the policy came to force, gets to be processed first. This gives an opportunity for many to think that either you have been consulting a good fortune teller, or busy influencing policy.

8. 3G Auction (2010)

The process of auction of 3G spectrum started in the year 2008 when the DOT formally announced the guidelines for auctioning 3G spectrum on 1st Aug 2008. But the auction could only start on 9th April 2010 (after 2 years) and concluded on 19th May 2010. Why? As spectrum was not available in the 2100 MHz band (3G band). But why was the 3G spectrum not available? The reason — the band was occupied by the defense and they won’t release it unless the DoT delivered their NFS (Optical fiber network). The DoT had promised to deliver this long back, but the project got unnaturally delayed. The defense was also annoyed with DoT as a large chunk of the spectrum in the 1800 MHz band was forcefully taken away from them to be assigned to the new 2G licenses of 2008, without the DoT keeping up on their promise on NFS. [If this was not the case then why did the DoT in the 2012 auctions (just after cancellation of licenses) put up only 295 MHz of 1800 MHz band for sale? That too when it admitted to TRAI in its reference dated 10th July 2013 (clause 2.1 of page 3 of TRAI’s recommendation dated 9th Sept 2013), that 413.6 MHz was released as a result of quashing of licenses in the 1800 MHz band?]. One might recall that the GOM (Group of Ministers) in 2003, which was constituted to look into the WLL issue, was informed about the heavy usage of mobile spectrum bands by the defense. The GOM recommended setting up a task force on working out modalities of releasing spectrum from the defense for the growth of mobile service. The task force was set up on 6th Oct 2003. So it is really frustrating to see that even after 7 long years the status quo remained and DOT could not get the defense to vacate the crucial mobile spectrum — all due to their poor execution on NFS. Since no one in the government took this issue seriously, DoT kept assigning spectrum in small increments based on subscriber-based criteria and allowed a large amount to lay waste, unused. In my view, the unavailability of the mobile spectrum is the key reason why DoT was forced to practice Adhoc policies for spectrum assignment in the past — which has led to these insurmountable problems of today which are extremely difficult for us to unwind.

8.1 PMO’s Intervened to Release 3G Spectrum

On 22nd May 2009, an MOU was signed between DoT and Defense. The purpose of the MOU was to set a roadmap for the release of the 2G/3G spectrum by the defense in lieu of DoT meeting some milestone on execution on the defense’s NFS network. The roadmap of the release of the spectrum that was decided in the MOU is laid out as under.

- 10 MHz in the 3G band (1920 to 1980) and 5+5 MHz in 2G band (1714–1734/1809–1829) after the signing of the MOU.

- 5 MHz in the 3G band on placing supply order for NFS and promulgation of defense band and defense interest zone.

- 5 MHz in the 3G band and 5+5 MHz in the 2G band on the supply of equipment ordered.

- 5 MHz in the 3G band and 5+5 MHz in the 2G band after installation of equipment.

- 5+5 MHz in 2G band on acceptance and testing and commissioning of the OFC network.

It looks like that as per the MOU only 10 MHz of spectrum in the 3G band was released immediately and not anymore. As DoT could not meet other items of the MOU within the target date of the 3G auction. This 10 MHz was grossly insufficient as 5 MHz of this was already given to BSNL/MTNL, leaving only one slot available for auction. Note BSNL/MTNL got 3G spectrum one year before the other private players did. Then how did the GOI managed to get 3 slots of the 3G spectrum to auction on 9th April 2010? It was due to the direct intervention of the PMO. Now you know why the DoT could not manage to get more 3G slots when there were twelve 3G (Total 2x60 MHz) slots available theoretically. This scarcity of 3G spectrum along with the entry of subsidized 2G license in 2008, created a huge demand and supply mismatch — leading to the exponential increase of price in the 3G auction — driving the reserve price from Rs 3500 Cr to Rs 16,400 Cr for 5 MHz of 3G spectrum — a 4.7 times increase.

8.2 The New Players Bid at Par

The auction's intensity can be seen from the fact that new players (some without 2G spectrum — eg Tata in Delhi) kept bidding till the end of the auction. See the picture below.

Out of 183 rounds (which lasted for more than 2 months), Aircel bid 113 times in Delhi and 116 times in Mumbai, lost. Similarly, Tata bid 95 times in Delhi and 84 times in Mumbai and lost. This intense bidding caused the price to increase so much that Delhi & Mumbai saw a 10 times price increase even when its combined % Revenue Share (of Pan India) was just 14%!

8.3 Operator’s Bid Intensely in the Last Rounds

Each rectangle in the above figure represents an operator. Each dot within the rectangle indicates an operator making a positive bid for a specific circle plotted on the Y-Axis of each rectangle. One can clearly see the increased density of these dots during the latter part of the auctions. This looks odd, isn’t it? Why would the bidders bid in every round when they didn’t in the earlier phase of the auction? The culprit was the auction “closing rules” defined in the NIA (Notice Inviting Applications). This rule had designed the auction to end abruptly once the “activity factor” was set to 100%. Hence, to ensure a win, the bidders were forced to bid in every round to ensure a win (not knowing when the auction will end). This forced the price of important circles like Delhi and Mumbai to every high (40% of the auction value).

8.4 Operator’s Bid to Prevent Customer Churn

The 3G auction was not a bid for just spectrum, it was a bid to preserve the value of their existing investments — incumbents with 2G subscribers, and new players with subsidized 2G spectrum. Therefore, a normal spectrum auction became an auction for survival. This is where the CAG in 2010 went terribly wrong when they estimated loss to the exchequer using the 3G auction price as reference. Any economist will tell you that unless the competitive dynamics of the market get challenged, the 2G spectrum that was given free or a subsidized rate would have attracted a fraction or no value. Why? At the end of the day, it is all about preserving market competitiveness. The operators will use all the means available to them to ensure that. Unfortunately, the 3G spectrum auction just became a means. Hence, the price that emanated out of 3G auctions should never have been used as a reference for determining the reserve price of future auctions. Doing so only increased the barrier to entry of new players in the market, and only helped the incumbents to preserve their market competitiveness. This was bad for the consumers, as their choice decreases, and the incumbents became complacent and did not care much about extending network coverage and improving the quality of service.

The following picture provides a birds-eye view of the operator’s PWB (Provisional Winning Bids) for the last — 183rd round. The winning prices were slightly lower as the winner needed to match the lowest value of PWB of that circle. The “bid” and “no-bid” markers tell us who continued to bid till the last round. One can clearly see that the operators focussed their wins only in those circles where they had to preserve their existing 2G competitiveness.

Total Outflow: Rs 50,630 Cr for 3 to 4 slots of 5 MHz each. Bharti @ Rs 12,295 Cr, Vodafone @ Rs 11,617 Cr, Idea @ Rs 5,768 Cr, Aircel @ Rs 6,499 Cr, RCOM @ Rs 8,585 Cr and Tata @ Rs 5864 Cr. MTNL & BSNL was assigned a block of 5 MHz in the 2100 MHz band earlier and was asked to pay Rs 16,750 Cr. Hence total inflow to the government was Rs 67,381 Cr. For individual prices discovered for circles, you can refer to my earlier note “Spectrum Auction Price Trends”.

Circle-wise & operators-wise outflows for 3G and BWA auctions are listed in the table below.

8.5 Total Spectrum:

The summary of total Spectrum acquired through both 3G and BWA auctions is listed as under (Note that quantum of BWA spectrum has been halved to align with 3G spectrum). BWA is TDD (time division duplex) and 3G is FDD (Frequency Division Duplex) spectrum.

No spectrum was left unsold in the 3G and BWA auctions.

8.6 License Fees -

3G was an auction of spectrum and not a license, and hence the power to offer 3G service emanated from their existing license. DoT just amended the license to include a 3G spectrum into it and kept all other conditions the same. Hence, the Revenue Share % on license fees remained the same as before.

8.7 WPC Royalty (Spectrum Usage Charge) —

Ideally, once spectrum is offered through an auction there shouldn’t be any revenue share attached to it, or even it is there, it should be just to cover administrative costs. But do you know that the SUC for the 3G spectrum is charged at the same rate as 2G (more 2G spectrum you have higher the license fees you pay for 3G spectrum) and that of BWA @ 1% of that revenue which only emanates from the BWA spectrum of 2300/2500 MHz? (See BWA UASL Amendment Dated — 7th Oct 2010). Strange isn’t it? Before 3G auctions, the royalty rate for 2G spectrum up to 2x4.4 MHz was 2% and 3% up to 2x6.2 MHz. DoT increased the same by 1% across all slabs, and that too arbitrarily, and decided to charge revenues emanating from 3G at the same rate of 2G (See 3G UASL Amendment Dated — 22nd Sept 2010). The logic for charging 3G at the same rate as 2G was because the revenues from 3G cannot be separated out from 2G, but then how can the revenues from 4G (BWA) separate out from 2G? It is clear that this was flawed logic, and did put 3G at disadvantage compared to 4G at 2300/2500 MHz spectrum. After that, it became a norm to charge all spectrum, other than the 2300/2500 MHz BWA spectrum @ 2G spectrum SUC. Readers who are interested to know more can read my notes titled — “History of Spectrum Usage Charge for 3G & BWA Spectrum”, “The Story of Spectrum Usage Charge — Past, Present, & Future” & Different Operators Will Pay Different Spectrum Usage Charges.

8.8 Key Issues -

Faulty Auction Design- Though the 3G auction was one of the best- executed and managed spectrum auctions in India, it had many design issues. a) Closing Rules — This rule was defined such that the auction could have ended abruptly once the activity factor (a metric set by the auctioneer to increase the intensity of bidding) was set to 100% and excess demand (Demand minus Supply) in all the circles for a particular round was Zero or negative. This rule forced the operators to keep bidding in most rounds even though some were provisional winners in the earlier rounds, and there was no need for them to bid in the next round. They did so due to the fear of being knocked out by others, thereby increasing the overall price of the auctions. b) Demand & Supply Mismatch — This was especially true for metro and category A circles, and very important as the auctions were being held just after the issue of new 2G licenses were give by DoT on subsidy @ 2001 prices — resulting in increased enthusiasm of the new players to bid aggressively. c) No Spectrum Roadmap — The operators bidding had no clue when the next 3G spectrum auction will happen. As stated above, the PMO, with great difficulty was able to get only three 3G slots for the Pan India assignment, and the defense was unlikely to vacate anything more, as DoT’s progress on NFS was very poor. Hence, lack of visibility on the next opportunity, the operators bid as if there was no tomorrow.

Favorable Rules for BWA — 3G auction process drove more favorable rules for BWA spectrum (like lower SUC, and Reserve price). This was totally unwarranted and demonstrated the bias of the regulators to pick winners than to nurture the market to allow the best technology to win. This is in the interest of all including those of the regulators.

9. BWA Auction (2010)

The BWA auction started after 2 days of the ending of the 3G auction, i.e on 24th May 2010, and concluded on 11th June 2010. But before we dwell on the details of the auction let’s figure out the history of the availability of the BWA spectrum in the 2300/2500 MHz bands. The story of BWA is similar to that of CDMA. It was earlier referred to as WiMAX band, just like the 2100 MHz was referred to as a 3G band. But later TRAI coined the term BWA (Broadband Wireless Access) to give it a technology-neutral flavor. WiMAX was pushing for the opening up of the 2500 MHz band, but unfortunately, there was no spectrum available there. The reason — one slot of 20 MHz was given to BSNL/MTNL one year in advance, just like they were given 2x5 MHz of 3G spectrum in the 2100 MHz band. And rest of the 2500 MHz band was occupied by the department of space (DoS), and they refused to make it available. Therefore, DOT had no choice but to open up the 2300 MHz band for BWA. WiMAX lobby was very disappointed as there was no WiMAX equipment functional in the 2300 MHz band, and therefore they decided to skip the auction. But all the efforts to drive regulatory advantage to the BWA spectrum, like lower SUC, and lower Reserve Price (BWA spectrum reserve prices was set 25% that of 3G) is now being leveraged by 4G.

But how did the 2300 MHz band got opened, when there was no BWA technology functional in that band? This story is interesting. Qualcomm introduced a new technology called UMB (Ultra Mobile Broadband) in the year 2007. To test this technology in India Qualcomm requested the WPC trial spectrum in the 2300 MHz band. WPC (Wireless Planning and Coordination Committee) had this reference. Hence, when it became impossible to open up the 2500 MHz band even after repeated attempts, it decided to open up the 2300 MHz band for auction. Then in order to boost confidence in the operators (about availability of optimal technology in 2300 MHz), Qualcomm decided to participate in the BWA auctions. Due to the paucity of the 3G spectrum, some bidders took the BWA spectrum in those circles where they could not get the 3G spectrum, and hence the BWA auction prices also skyrocketed. The following picture provides a birds-eye view of the final increase when compared to the reserve price.

Note - the price of 2300 MHz (unpaired) has been doubled for each circle to align it with the 2100 MHz paired spectrum.

9.1 Players Bid to fill up 3G holes

In the BWA auction, the intensity was quite high if not comparable to the 3G auctions. Only 2 slots of 20 MHz were up for grab and the final bidding was mainly among four bidders — RJIO, Bharti, Qualcomm & Aircel.

9.2 Operators Bid Very Intensely

The impact of the closing rules was felt in this auction as well. However, some bidders like Infotel (now RJIO) had bid very overenthusiastically. This clearly evident by the increased density of dots in the above picture. This led to a disproportionate price increase.

The following picture provides a birds-eye view of the operator’s PWB (Provisional Winning Bids) for the last — 117th round. The winning prices were slightly lower as the winner needed to match the lowest value of PWB of that circle. The “bid” and “no-bid” markers tell us who continued to bid till the last round. One can clearly see that the Bharti focussed their wins only in those circles where they could not win the 3G spectrum.

9.3 Total Outflow: Rs 25,695 Cr for 2 slots of 20 MHz each. Bharti @ Rs 3817 Cr, Aircel @ Rs 3438 Cr, Tikona Rs 1058 Cr, Qualcomm @ Rs 4533 Cr and RJIO Rs 12,847 Cr. MTNL & BSNL was assigned a block of 20 MHz in the 2500 MHz band earlier and was asked to pay Rs 12,847 Cr. Hence total inflow to the government was Rs 38,543 Cr. For individual prices discovered for circles, you can refer to my earlier note “Spectrum Auction Price Trends”.

9.4 Key Issues -

Faulty Auction Design — For the BWA auction same design issues were applicable as were for 3G. Less than adequate spectrum, closing rules, and no roadmap for future spectrum, etc.

Similar Spectrum But Different Rules — BWA spectrum auctions were marred by the issue of DOT setting favorable rules for BWA technologies compared to 3G. There was no logic to the decision to charge a lower SUC (Spectrum Usage Charge) for BWA when its quantum was much higher when compared to 3G (2x5 MHz vs 20 MHz). Also, there was no logic to set the reserve price of BWA to 25% that of 3G (though it didn’t matter much later as auction prices exploded). As mentioned earlier all this happened effective lobbying by the WiMAX lobby who positioned BWA for rural broadband (see ET article dated 5th Jan 2009 —WiMax: Complementary not competitive), and we know the intent was just the opposite. The effect was so entrenched that even after so many years, DoT is still charging the BWA spectrum @ 1% when all other spectrum bands are charged at the rates of 2G (3% or higher). Read my earlier note which describes this situation titled — Different Operators Will Pay Different Spectrum Usage Charges.

For further details on 3G & BWA auctions, you can visit my web page — https://paragkar.com/2010-2/

10. Spectrum Auction (2012)

The 2012 auction started on 12th Nov 2012 and concluded on 14th Nov 2012 (in just 2 days). In the 2012 auction, only 800 & 1800 MHz bands were offered for sale. The spectrum in these bands got released due to the cancellation of license ordered by the SC judgment dated 2nd Feb 2012. In this judgment, the SC ordered the cancellation of all licenses granted by Raja (except the dual technology ones) and directed the government (on page 93, clause iii) to hold fresh auctions for spectrum in 2G bands as was done for the allocation of spectrum in the 3G band in 2010. But, the SC didn’t cancel the dual technology licenses of Reliance & some others because the rules were set such that the dual technology companies did not require a separate license to get access to the spectrum for the 2nd technology. They simply had to pay up entry fee (Pan India Rs 1650 Cr) one more time to get that access.

10.1 Liberalization of 2G Bands

With SC seeking the auction of 2G spectrum, and directing the TRAI to recommended the modalities, and the TRAI while doing so (in its recommendation dated 23rd April 2012), gave a new twist to the definition of the existing 2G spectrum, which was earlier assigned administratively, i.e bundled with the license and based on subscriber-based criteria. To date, we all had an understanding that UAS License is technology-neutral and can be used to deploy any technology, which TRAI also agreed, but TRAI interpreted the WOL (Wireless Operating License) as technology-specific — can be used for deploying only GSM or CDMA technologies. Why? Clause 43.5(i) of the then UASL says the following.

“This license agreement does not authorize the right to use spectrum. The methodology and procedure for allotment shall be prescribed by the licensor/WPC from time to time. for the spectrum to be granted by WPC, as per the prescribed plan.”

The WPC’s Prescribed the following plan for spectrum assignment.

“For wireless operations in the SUBSCRIBER access network, the frequencies shall be assigned by the WPC wing of the DoT from the frequency band earmarked in the applicable National Frequency Allocation Plan in coordination with various users. Initially, a cumulative maximum of up to 4.4 MHz + 4.4 MHz shall be allocated in the case of TDMA based system @ 200 kHz per carrier or 30 kHz per carrier, or a maximum of 2.5 MHz+2.5 MHz shall be allocated in the case of a CDMA based system.”

So as per the above clause, TRAI concluded that the operator can deploy only GSM technology in the 900/1800 MHz band, and CDMA in the 800 MHz band. Hence, TRAI recommended that the spectrum in these bands must be reframed and assigned through auction in the next available opportunity.

Operators watched helplessly

But why? Because they themselves were partly responsible for this mess. As in the past, the GSM operators never advocated for the change of subscriber-based spectrum assignment policy. And the CDMA operator committed their part of the mistake by emphasizing CDMA’s spectral efficiency superiority in the courts as one of the arguments to strengthen their case on accessing “full mobility”. For the GSM operators, the administrative assignment of spectrum based on subscriber-based policy was a useful tool to keep CDMA operators contained and not let them fully leverage their technological potential of offering mobile internet services, as was being used globally at that time.

If this was not true why in 2005, Sunil Mittal openly criticized Ratan Tata when he offered to pay Rs 1500 Cr for 2x5 MHz of the 3G spectrum? In one of the interviews with CNBC (anchored by Sareen Bhan, during that time), the CEO of a GSM company even suggested that he may be allowed to take 5 MHz of 3G spectrum in the 2100 MHz band, in lieu of 2G spectrum in the 1800 MHz band, as the subscriber numbers that he possessed at that time, made him eligible for 2x15 MHz spectrum in the 900/1800 MHz band, as he was holding just 2x10 MHz. Also, refer to the article dated 1st June 2005 in the business standards — “Who’s right, Tata or Mittal?” to get further insight on this issue.

Also, at that time the government had the preception that incumbents were making huge profits, and their cry for GOI charging high license fees were nothing but “crocodile tears”. The reason — a) Just to entice the investors, listed operators were regularly publishing their profits numbers, b) In 2010, Bharti made a huge investment in Africa ($9 billion USD) — leading the government to believe that more can be extracted from the industry in terms of license fees.

10.2 Reserve Price

The reserve price for the 2012 auctions was recommended by TRAI by taking 3G auction prices as a reference. Bandwise logic used by them to arrive at the reserve prices is described as under.

a) 1800 MHz band — As per TRAI, the 1800 MHz is 1.2 times more efficient (from a propagation point of view) compared to the 2100 MHz (3G band). And since the 3G auction happened 2 years back, these prices needed to be indexed by an average SBI PLR of 12.63%. Also, to arrive at the final reserve price from the auction price, one needs to discount it by 20%.

b) 800/900 MHz band — Now as per TRAI, the sub GHz band 800/900 MHz is two (2) times more efficient compared to the 1800 MHz band. Hence, to arrive at the reserve price of these bands, the 1800 MHz reserve price just needs to get multiplied by 2. However, it is worthwhile to note that TRAI in its earlier recommendation on 11th May 2010 (Clause 6.93 page 298) had suggested a multiplying factor of 1.5. When DoT asked for clarification TRAI responded on 12th May 2012 (Page 41) by saying that they have done so as the market conditions have changed. Also in the same clarification, TRAI reduced the multiplying factor for 800 MHz (Not 900 MHz) from 2 to 1.3. This was further reduced by DOT to “<1”, i.e almost at par with the 1800 MHz price that TRAI had recommended. Why? The reason — the quantum of spectrum available for the 2012 auction in the 800 MHz band is less than 2x5 MHz in some circles (page 42), so as per TRAI it was not possible for the operators to offer fully liberalized service. But soon (in the very auction and just four months later), the same 800 MHz was offered in blocks of 2x5 MHz for the 2013 auctions (in 14 of the 22 circles), then why didn’t the regulator/DoT restored the multiplying factor of 800 MHz back to “2”? This is when in the same auction, for arriving at the reserve price for the 900 MHz, the multiplier factor of “2” was used? Then later, in 2016, the wrong multiplier factor of “4” was picked up for arriving at the reserve price of the 700 MHz (more on this as you read through) — making the 700 MHz lying idle for the last 11 years — what a waste (Note — the 700 MHz band was first discussed by TRAI in its 2010 recommendations). This is Bizarre!

c) 2100/2300 MHz band — To arrive at this they just indexed the 2010 3G/BWA auction price by the SBI PLR of 12.63%.

d) 700 MHz band — Strangely, the TRAI used totally different logic to arrive at the reserve price for the 700 MHz. This is when the TRAI acknowledged that all the bands listed above are capable of deploying 4G technology. Not only that TRAI committed a serious mistake of using a wrong multiplying factor of 4 than of 2.3 — the factor that emanated out from their own logic. Though it didn’t matter at that time, however, later in the 2016 recommendation the TRAI picked up this recommendation totally out of context to multiply the 1800 MHz reserve price by 4 to arrive at the reserve price of 700 MHz (Clause 3.75 Page 97 of TRAI Reco dated 27th Jan 2016). It did not even refer to the fact that all pricing recommendations of TRAI in 2012 were later revised (lowered) by the DoT (700 MHz band price was left untouched by DoT as it was not up for auction), and TRAI in its recommendation dated 9th Sept 2013 (page 85) concluded that valuation of spectrum in India cannot be done on the basis of international prices. [Note in 2012 (page 104, dated 23rd April 2012), the TRAI recommended the factor of “4” based on international spectrum prices, then why in 2016 it the TRAI chose to refer to the faulty recommendation of 2012?] Also, at the time when this decision for the multiplier factor of “4” was taken, the DoT didn’t even finalize the band plan for 700 MHz (page 28 of TRAI’s recommendation dated 15th Oct 2014). Then when it did put the band for auction for the first time in 2016, we all know what happened — there were no takers for this spectrum even in the 2021 auction even when TRAI reduced the band price by 50%. And to date, the consumers of our country are deprived of this valuable spectrum — which could have been used to connect rural India for its better propagation characteristics — much better than any other band. I had described this issue in my earlier notes titled — Is TRAI’s 700 MHz Price Outcome of an Inadvertent Error? & Pricing Rationale of 700 MHz.

Here is the summary of all the reserve prices originally recommended by the TRAI.

The final reserve prices that went for auction were reduced by DoT in most circles than what TRAI had recommended. The price that emanated out of the auctions along with the reserve prices is described below in the charts below.

From the above charts, one can see that some spectrum was taken in the 1800 MHz band, but the 800 MHz price (even after so much reduction both by TRAI and then DoT) was considered too high by the bidders and therefore there were no takers.

10.3 Bidding Intensity Was Very Low

The following is the “bidding matrix” of the 2012 auction of the 1800 MHz band.

The auction was a subdued affair and got over in 14 rounds and most of the spectrum remained unsold.

The Operator wise outflows are available in the chart below (Rs Cr). Note that though the bidding was less intense, Voda Idea’s bids in many circles for a very small quantum of spectrum. This established the market price for these circles, thereby becoming the reference price for future auctions.

10.4 Total Spectrum Sold/Unsold -

The following chart provides that information. One can see a large quantum of spectrum (57% of the total offered ) remained unsold (167.5 MHz out of the offered 295 MHz) in the 2012 auctions.

The following picture gives a better graphical view of the sold and unsold spectrum.

10.5 The intensity of Auction-

One can see that intensity of the auction was very low. The whole auction got over in 14 rounds, compared to 183, & 177 rounds for 3G and BWA auctions. The operator's total number of bids was very low compared to the 2010 auctions. The following chart provides the details.

Bharti just bid once in Assam and won, and Voda had to bid 3 times in Bihar as there seems to be some competition there.

10.6 License Fees & Spectrum Royalty —

The License Fees were the same as was describes earlier but it was decided that Spectrum being allocated via this auction will be added to the administrative spectrum for determining the slab for Spectrum Usage Charges (See NIA Page 35).

10.7 Key Issues —

- TRAI’s recommendation of 2012, fundamentally altered the definition of the administrative spectrum and branded it as technology non-neutral. This came as a rude shock to the operators as they have been paying SUC (Spectrum Usage Charge) on that spectrum anyways.

- TRAI’s recommendation of using 3G auction prices as reference was totally wrong, given the circumstance that the auction happened (I have described this earlier). This bumped up the spectrum prices to unrealistic levels.

- TRAI’s recommendation permanently set the practice for taking the duly indexed last auctioned price as reserve price for all future auctions with just one exception in 2013 (when this practice was temporarily suspended). This is when TRAI in the same recommendation (Clause 3.83, Page 100) stated that “A study of various auctions held globally in last 3–4 years reveals that the reserve prices are generally around 0.5 times the final prices. However, in the context of the Indian telecom sector, where the demand for spectrum is considerably higher, the authority has decided to use a factor of 0.8 to determine the reserve price.” Now if the price discovered in 2010 (which was duly indexed) was to be seen as the final price, then why was the final price for 2100 MHz (recommended by TRAI) was not reduced by the factor of 0.8? The contradiction was clearly visible, as the TRAI used this factor for all other bands whose price was extracted for the same 2100 MHz last auction price duly indexed!

- TRAI destroyed the 700 MHz band, by making such gross mistakes — both in logic and calculation. This was picked up again by the TRAI in 2016 without application of mind. Also, none of the operators complained about it by pointing to the out-of-context application of 2012’s recommendation which had a serious mistake and was made in a casual manner. Nothing can be more bizarre than this!

- TRAI recommended the 900 and 1800 MHz spectrum to be auctioned in a block size of 1.25 MHz, this was wrong as it resulted in wastage of spectrum. Later this decision of TRAI was reversed and the block size of the 900 & 1800 MHz spectrum was changed to 0.2 MHz.

- TRAI changed the rules of auction fundamentally but proposing a deferred payment option (table 3.10 page 116) for spectrum won through auctions. This created a perpetual revenue stream for the government on top of the license fees and SUC, thereby totally defeating the purpose of delinking spectrum from the license.